Elections

Main navigation

Female MEPs have been warned of the threat of deep-fake explicit images being used against them in the upcoming elections.

There are now serious concerns that women running in the EU elections could be targeted with AI generated nude photographs or fake videos of them in compromising positions.

Sitting MEP Maria Walsh described the prospect of deep-fakes as "terrifying" and has urged voters to be aware of AI generated content that may be used to discredit candidates.

"It's about having conversations, educating people about what is real and what is not and it's really to be aware of the impact AI has and can have on politics," she said.

She added: "It is terrifying, I'm not going to lie. I would be nervous as a young female politician."

Read here the full article published by the Irish Examiner on 8 April 2024.

Image source: Irish Examiner

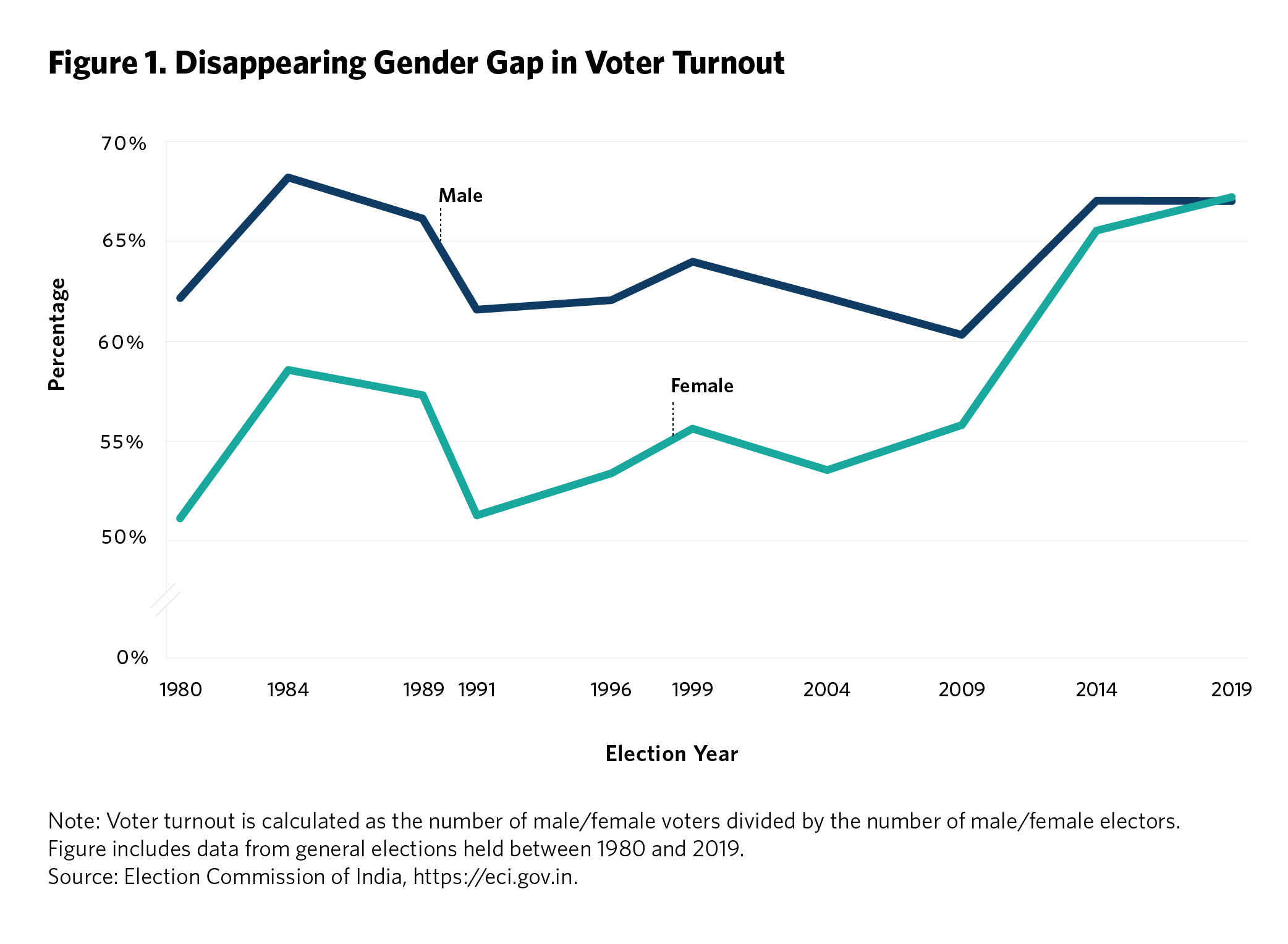

In India, as in many democracies around the world, there has long been a discernible gender gap in citizens’ political participation. For decades, Indian men were significantly more likely to cast their ballots on election day compared to women. It is noteworthy, therefore, that in the country’s 2019 general election, the historic gap between male and female turnout came to an end; for the first time on record, women voters turned out to vote at higher rates than men (see figure 1). Predictions for India’s upcoming 2024 general election suggest that this trend is likely to continue.

Although the gap between male and female voter turnout in India has been gradually shrinking in recent years, the convergence in electoral participation is nevertheless surprising for multiple reasons. First, as noted by Franziska Roscher, the increase in female turnout in India is occurring while female labor force participation—an important driver of women’s political participation—remains low compared to peer economies. Second, national-level data from the National Election Study (NES), conducted by the Lokniti Program of the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, and other smaller studies confirm that women lag men across all measures of nonelectoral political engagement. For instance, data from two separate primary surveys—conducted in Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh by political scientists Soledad Prillaman and Gabrielle Kruks-Wisner, respectively—demonstrate that while the gender gap in voter turnout has closed, gaps are all too visible in other forms of sustained political engagement, such as contacting elected representatives, attending public meetings, and participating in campaign activities. Third, women continue to be underrepresented in India’s national parliament and its state assemblies.

Read here the full article published by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace on 5 April 2024.

Image source: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Washington — When Suriya Bibi was running for a seat earlier this year on the Khyber Pakhtunkwa provincial assembly, she faced numerous challenges beyond being a woman and hailing from a minority sect in Pakistan's remote district of Chitral.

Another obstacle appeared when the Election Commission randomly assigned a hen symbol as her identifier on ballot papers — such symbols are tools to aid illiterate voters. In January, Pakistan's Supreme Court barred her political party, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, or PTI, from using the cricket bat symbol associated with former Prime Minister Imran Khan.

The hen symbol inadvertently perpetuated the stereotype that women in Chitral were better suited for poultry farming than politics. Her opponents capitalized on their good luck, ridiculing her and mocking the symbol's association with domesticity.

In a phone interview with VOA, Bibi said that there was no shame in poultry farming and rejected the attempt to diminish her worth based on her election symbol.

Read here the full article published by Voice of America on 23 March 2024.

Image source: Voice of America

It’s presidential campaign season in Senegal’s capital city and all over town the candidates’ faces beam down at voters from posters tacked to light poles and plastered on billboards. Eighteen people are running, and at times, their images seem to blend together: a sea of older men in dark, dour suits. But one face stands out.

In her pastel blue headwrap and green dress, Anta Babacar Ngom cuts a strikingly different figure. For one thing, at 40 years old she’s a generation younger than many of the other candidates. For another, she’s a she.

Although no one expects Ms. Ngom to become the next president, her presence in the race speaks to the increasingly forceful role of women in the politics of Senegal, which has one of the highest percentages of female legislators in the world.

Read here the full article published by The Christian Science Monitor on 22 March 2024.

Image source: The Christian Science Monitor

NEW DELHI: With more women participating in voting than ever before and even dominating political discourse within their households, they now find themselves at the forefront of various schemes and policies announced by political parties ahead of elections.

Aam Aadmi Party govt announced Mahila Samman Yojana in the budget, promising a monthly stipend of Rs 1,000 to women above 18 years of age, and proudly promotes their free travel in public buses.

Similarly, BJP recently launched the ‘Lakhpati Didi’ programme, aiming to make women financially self-reliant while promoting various other women-centric schemes implemented in recent years. This is perhaps the first time that BJP has fielded two women candidates in the capital.

Political analysts agree that with a higher voter turnout in parliamentary as well as assembly polls in recent elections, women will now drive the narrative ahead of all elections.

Click here to read the full article published by The Times of India on 18 March 2024.

Image source: The Times of India

Introduction

Over the last twenty years, the world has witnessed significant shifts towards greater gender equality in politics, which in turn has had positive implications for democracy and society at large.

Mexico has witnessed a systematic incorporation of gender perspective, equality, and parity in public life, signifying a transformation of women's ability to participate in the country's future. The prime example is the National Electoral Institute (INE) mandate, later ratified by the Electoral Tribunal (TEPJF), for political parties to guarantee gender parity in all upcoming gubernatorial elections of 2024: Chiapas, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Morelos, Puebla, Tabasco, Veracruz, Yucatán, and Mexico City.

Unfortunately, as women's participation in politics rises, an increase in political violence that explicitly targets women has also occurred. The 2020-2021 electoral process was the most violent against Mexican women.

Mexico´s political system is awash with political violence that explicitly targets and affects women, obstructs social justice, and hinders democracy. The advances in female political participation have been met with resistance as men, territorial interest groups, and political elites seemingly feel threatened by increasing female power and respond with violent actions to uphold the traditional system of politics to deter women’s independent participation.

Read here the full article published by the Wilson Center on 13 March 2024.

Image source: Wilson Center