Elections

Main navigation

It’s presidential campaign season in Senegal’s capital city and all over town the candidates’ faces beam down at voters from posters tacked to light poles and plastered on billboards. Eighteen people are running, and at times, their images seem to blend together: a sea of older men in dark, dour suits. But one face stands out.

In her pastel blue headwrap and green dress, Anta Babacar Ngom cuts a strikingly different figure. For one thing, at 40 years old she’s a generation younger than many of the other candidates. For another, she’s a she.

Although no one expects Ms. Ngom to become the next president, her presence in the race speaks to the increasingly forceful role of women in the politics of Senegal, which has one of the highest percentages of female legislators in the world.

Read here the full article published by The Christian Science Monitor on 22 March 2024.

Image source: The Christian Science Monitor

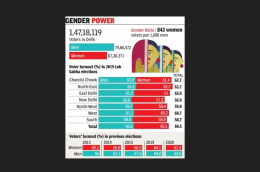

NEW DELHI: With more women participating in voting than ever before and even dominating political discourse within their households, they now find themselves at the forefront of various schemes and policies announced by political parties ahead of elections.

Aam Aadmi Party govt announced Mahila Samman Yojana in the budget, promising a monthly stipend of Rs 1,000 to women above 18 years of age, and proudly promotes their free travel in public buses.

Similarly, BJP recently launched the ‘Lakhpati Didi’ programme, aiming to make women financially self-reliant while promoting various other women-centric schemes implemented in recent years. This is perhaps the first time that BJP has fielded two women candidates in the capital.

Political analysts agree that with a higher voter turnout in parliamentary as well as assembly polls in recent elections, women will now drive the narrative ahead of all elections.

Click here to read the full article published by The Times of India on 18 March 2024.

Image source: The Times of India

Introduction

Over the last twenty years, the world has witnessed significant shifts towards greater gender equality in politics, which in turn has had positive implications for democracy and society at large.

Mexico has witnessed a systematic incorporation of gender perspective, equality, and parity in public life, signifying a transformation of women's ability to participate in the country's future. The prime example is the National Electoral Institute (INE) mandate, later ratified by the Electoral Tribunal (TEPJF), for political parties to guarantee gender parity in all upcoming gubernatorial elections of 2024: Chiapas, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Morelos, Puebla, Tabasco, Veracruz, Yucatán, and Mexico City.

Unfortunately, as women's participation in politics rises, an increase in political violence that explicitly targets women has also occurred. The 2020-2021 electoral process was the most violent against Mexican women.

Mexico´s political system is awash with political violence that explicitly targets and affects women, obstructs social justice, and hinders democracy. The advances in female political participation have been met with resistance as men, territorial interest groups, and political elites seemingly feel threatened by increasing female power and respond with violent actions to uphold the traditional system of politics to deter women’s independent participation.

Read here the full article published by the Wilson Center on 13 March 2024.

Image source: Wilson Center

In our pursuit of gender equality, the Council of European Municipalities and Regions (CEMR) is committed to exposing the hurdles faced by women in local and regional politics. Our recently released report, “Women in Politics,” provides a visual snapshot of women’s representation in elected roles across subnational levels.

A detailed breakdown of portfolios at the local level underscores the challenges that persist. The infographics also unveil the outcomes of an anonymous CEMR survey involving 2,424 participants from 31 countries. Focused on elected women in local and regional European roles, the survey delves into their experiences of violence in the political realm. These findings shed light on a disturbing reality: violence against locally elected women is a prevalent issue that demands urgent attention.

“Empowering women at the local level is pivotal in our journey towards gender equality. The ‘Women in Politics’ report, accompanied by insightful infographics and a comprehensive survey, reflects our commitment to understanding and addressing gender inequalities. Together, through the power of grassroots movements, we can build a more inclusive and equitable future for all.” – CEMR President Gunn Marit Helgesen.

Read here the full article published by Euractiv on 8 March 2024.

Image source: Euractiv

Earlier this year, the IPU announced that around 70 elections were slated to take place in 2024, in what has been dubbed a super election year. In total, thousands of parliamentary seats are up for grabs. As of March 2024, women’s representation in parliament stands at just 26.9%. There was some progress in 2023 – 0.4 percentage points year on year, but progress has slowed compared to previous years.

Will that have changed by the end of this high-stakes election year?

The extent to which women's representation will improve in the countries that go to the polls in 2024 will depend on a variety of factors. But there are some steps that countries can take to advance progress.

IPU’s analyses over the years have shown that two factors play an influential role: the existence of well-designed quotas and the type of electoral system. Specifically, proportional representation and/or mixed electoral systems tend to enable a higher representation of women compared to plurality/majority systems.

According to the IPU's latest estimates, of the parliamentary chambers due to hold elections in 2024, 27 use PR/mixed systems, 24 use plurality/majority systems and 47 use some form of quotas.

Read here the full article published by the Inter-Parliamentary Union on 6 March 2024.

Image by IPU

In 1906, Finland became the first country in Europe to grant women the right to vote, with the adoption of universal suffrage, at the same time as it won its autonomy from the Russian Empire. The following year, Finnish women were able to exercise this right in the general elections. Throughout the twentieth century, women in Europe and around the world fought long and hard to gain the right to vote without any additional conditions to those required of men. In some countries, only widows were allowed to vote as a first step towards electoral emancipation (in Belgium, for example, until 1921). In other countries, such as Bulgaria, the right to vote was initially reserved for mothers of legitimate children and exclusively for local elections. In Portugal, only women with a university degree were allowed to vote from 1931 on. In Spain it was not until post-Franco democratisation and the 1976 elections that Spanish women regained the right to vote, initially acquired in 1931 before the civil war. This year France is celebrating the 80th anniversary of women gaining the right to vote. Cypriot women won the right to vote at the same time as their male counterparts when the Republic was created in 1960. This can be explained quite simply by the fact that, at that time, such discrimination could no longer be justified. So, it took a good part of the twentieth century to get there...

Read here the full article published by the Foundation Robert Schuman on 5 March 2024.

Image source: Foundation Robert Schuman