Women's Leadership

Main navigation

Countries all throughout the world struggle with providing equal opportunities and positions in regards to women when compared to their male counterparts (Brennan & Elkink, 2015). The People’s Republic of China is not an exception to this trend. In order to combat gender inequality in politics, a quota for women cadres was introduced in 1995. This would ensure that at least one woman holds a head or deputy position in regional governments (Jiang et al, 2023). Despite this quota, women in China still struggle to participate in politics. This statement will be supported by these following arguments; (1) The society and culture in China view women as subordinate, thus lacking support and belief in women when in leadership and political positions, (2) The few women that do end up in positions in government struggle to receive prestigious promotions compared to their male counterparts; and finally (3) In order to attain these promotions these women need to outperform and display similar characteristics to their male colleagues in order to attain similar positions. This issue is important to understand in order to see whether mere gender quotas are sufficient in solving gender inequality in politics or are there other factors we as a society must willingly work to fix.

Click here to read the full article published by Modern Diplomacy on 6 February 2024.

Image source: Modern Diplomacy

Women’s underrepresentation at all levels of government is a persistent problem in the United States. RepresentWomen’s research shows that although we have made progress towards parity, this progress is slow and inconsistent, meaning we are unlikely to reach gender balance within our lifetimes. Increasing and sustaining women’s leadership in elected office requires us to remove the barriers women candidates and legislators face. This drives our research at RepresentWomen to identify the barriers and system-level solutions we can implement to create a more representative, gender-balanced democracy.

Click here to read the full article published by LA Progressive on 22 November 2023.

Image by LA Progressive

The Gender Equality Index developed by the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) in 2013, is recognised in the European Union as an important tool for analysing the state of gender equality in a society as well as comparing current trends and the current situation at the European Union (EU) level. Since 2016, the Agency for Gender Equality of Bosnia and Herzegovina within the Ministry of Human Rights and Refugees of Bosnia and Herzegovina together with the Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina have been engaged in activities that have led to the development of a Gender Equality Index for Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Gender Equality Index for Bosnia and Herzegovina 2022 presents the full index scores for two full domains, Knowledge and Power and the partial index scores for the domains of Work and Health. With the development of this report, Bosnia and Herzegovina will for the first time be able to rely on a statistically legitimate, objective and up-to-date statistical tool for the comparison of the state of gender equality in the country wth countries in the region and in the EU. The combined efforts of the Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Agency for Gender Equality of Bosnia and Herzegovina within the Ministry for Human Rights and Refugees of Bosnia and Herzegovina, under the invaluable guidance of EIGE and supported by UN Women and financed by the European Union, have resulted in the development of this Gender Equality Index.

Click here to access the report.

Across Kenya, local conflicts driven by diverse factors have one thing in common: they’re increasingly being mediated by women. From ethnic tensions to land disputes, some of these conflicts stretch back decades; remaining unresolved despite the lasting instability and violence they create among communities. So women are stepping up to end longstanding strife through local dialogues and outreach, approaches male-dominated leadership has not always been willing to take. But in order to build lasting peace, they need support from both their communities and the state—which some are receiving, and many are not.

Old conflicts, new harm

In the country’s western region, longstanding tensions are driving new security risks in the neighbouring counties of Kisumu and Nandi. Their predominant ethnicities mirror the tribal background of the two leading presidential candidates in this year’s election, and the border region has been identified as a hotspot for elections-related violence.

Click here to read the full article published by UN Women on 24 October 2022.

After national news coverage of a COVID-19 mask requirement controversy in Dodge City, Kansas in December of 2020, Mayor Joyce Warshaw received numerous threats such as “Burn in hell”; “Get murdered”; and “We’re coming for you.” Fifteen days later, Mayor Warshaw resigned saying that she and her family no longer felt safe.

Four important questions arise from the circumstances in which Mayor Warshaw and other mayors find themselves.

- How prevalent is violence against mayors from the public?

- Are there gender and race-based differences in violent experiences of mayors?

- Is the violence experienced by mayors causing them to rethink their service?

- What are the wider implications to representation of exposing public servants to abuse and violence? Will fewer people, especially women and women of color run, for and stay in office?

This research seeks answers to these questions.

Click here to access the report.

More than 100 years after women gained full citizenship rights through the 19th Amendment, women are still under-represented in government. While it is widely known that no woman has become president, it is not only the highest executive offices where women have not had access: women also face barriers at the state level.

Even in 2022, the vast majority of state cabinets are dominated by men. Cabinet members hold a vital position of power: running state agencies and serving as trusted advisors to the governor, helping them make important decisions. In nearly all states, most, if not all, cabinet members are appointed by the governor.

Click here to access the report.

WARNING: PROFANE LANGUAGE

The fabricated sex videos posted online purportedly of Aika Robredo and Tricia Robredo, daughters of Vice President Leni Robredo, are among the recent cases of disinformation circulating in cyberspace that are framed in the vitriol of misogyny. The attack on the young Robredos is obviously an attempt to damage their mother’s bid for the presidency. Many are shocked but not surprised, given the increasingly heated campaign in which the only female candidate is perceived to pose a formidable threat to the nine other presidential aspirants, all male. That the disturbing fakery was not exactly unexpected indicates the alarming yet taken-for-granted consequence of any form of political engagement by women – both in the real world and in virtual space.

This analysis is premised on the observation that misogyny – the intense prejudice against and contempt for women – has become more ferocious in cyberspace in recent years, particularly against those critical of President Rodrigo Duterte, and now during the lead-up to the 2022 elections. This report analyzes a relatively small but significant sample of the appalling number of misogynistic memes, posts, and comments that fan the flame of misogyny, with an equally sickening number of likes and shares from like-minded users, from 2015 to 2020. The following will be discussed as I work through the argument that cybermisogyny violates human rights. It is a disruption of peace, an affront to dignity and equality, and a threat to safety and security. It jeopardizes women’s right to work. As it tends to silence women, cybermisogyny undermines democracy.

Click here to read the full article published by The Daily Guardian on 22 May 2022.

Political gender equality is a central pillar of democracy, as all people, independently of gender, should have an equal say in political representation and decision-making. In practice, democracies are generally better at guaranteeing gender equality than most non-democratic regimes. According to International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy Indices, 41 per cent of democracies have high levels of gender equality, while this is the case in only two of the world’s authoritarian regimes (Belarus and Cuba). The democracies with low levels of gender equality are also exceptional (only four, all weak democracies - Iraq, Lebanon, Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea). Low levels of gender equality are much more common in non-democracies – more than one third of them fall into this category.

Despite more than half the countries in the world being democracies of some form, levels of political gender equality have not kept pace with democratic progress. In 2022, only 26 per cent of legislators in the world are women, according to the Inter-Parliamentary Union. At the current rate, gender parity will not be achieved until 2062, according to International IDEA’s estimate. The proportion of women heads of state is even lower. In 2022, only 19 countries in the world have women in the highest office of executive power. Of these, all except four are democracies. Moreover, as global democratic progress is threatened by rising authoritarianism and democratic backsliding, fragile levels of gender equality, further weakened by the pandemic, are at risk of more setbacks, as gender is increasingly used as a weapon in such processes.

Click here to read the full article published by International IDEA on 7 March 2022.

Fawcett's Sex and Power 2022 Index is a biennial report which charts the progress towards equal representation for women in top jobs across the UK. Yet again, the report reveals the pace of change is glacial in the majority of sectors and shows that women are outnumbered by men 2:1 in positions of power.

Women of colour are vastly under-represented at the highest levels of many sectors and alarmingly, they are missing altogether from senior roles such as Supreme Court Justices, Metro Mayors, Police and Crime Commissioners and FTSE 100 CEOs.

Click here to download the report.

RepresentWomen's Arab State Brief reviews the extent to which women are represented in Arab countries, the history of Arab independence and revolutions - and their impact on women's rights and representation; and country-specific information that covers the history of systems reforms and their impact on women's political rights and representation in the region.

Click here to read the full report.

New Zealand was the first country in the world where women won the right to vote and it’s now a leader for gender parity in politics.

Following the October 2020 elections, Prime Minister Rt. Hon. Jacinda Ardern leads the most diverse government in New Zealand’s history. Today there are more women, people of colour, LGBTQ+ and indigenous MPs than ever before. This diversity is reflected in the 20-person Cabinet, of which eight members are women, five are Māori, three are Pasifika, and three are from the LGBTQ+ community. In New Zealand, the government now better reflects the diversity of its population, and it is forging a path for other nations to follow.

Click here to read the full article published by IPU.

With less than a decade to go to 2030, the deadline for the Sustainable Development Goals, women constitute just 11% of MPs and 18% of councillors in Botswana: well below the gender parity target and among the lowest proportions in Southern Africa.

This situation analysis of WPP in Botswana is part of the consortium's work and aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the state of women's participation in political decision making at all levels, including in political parties, the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) and the media.

Accelerating women representation in political decision making requires an inter-sectional approach involving government, civil society, the media, academia, the private sector, youth and men. The upcoming Constitutional Review- the first since independence in 1966 - provides a unique opportunity to re-write herstory in Botswana; review the electoral system with a gender lens, and adopt the special measures that have proven necessary in every country in the world that has succeeded in increasing WPP. The time is indeed now!

Click here to access the analysis.

Kamala Harris, Kirsten Gillibrand, Amy Klobuchar, and I all had better campaign win-loss records than any of the leading men. But the question was never whether a man could be elected. Despite our stronger records, it was always, “Can a woman win?” —excerpt from PERSIST by Elizabeth Warren (Metropolitan Books, May 2021).

“Why doesn’t she smile more?” “Could you see yourself getting a beer with her?” “Do people like her enough to win?” Every election cycle, questions like these become a common refrain when a woman—or more than one woman—runs for office. These inherently sexist questions come with revealing misogynistic expectations in politics, but also have real electoral consequences.

Women candidates are scrutinized and picked apart based on assumptions about their lack of appeal to voters. This constant debate about electability is detrimental to women’s candidacies and U.S. politics as whole, as it focuses on the quagmire of a candidate’s image rather than their policy positions. Men don’t need to be liked to be “electable”—women do.

What Does “Likability” and “Electability” Mean?

Likability is a key component of electability along with establishing a candidate’s qualifications. Often seen together, likability and electability refer to how a candidate is perceived by a voter and whether or not that voter believes they can win an election.

Click here to read the full article published by MS Magazine on 24 May 2021.

Fifty years after getting the right to vote, women are better represented in the Swiss parliament than ever. In a ranking of 191 countries worldwide, Switzerland is in 17th place. But this is deceptive: at the local level, representation is still low.

On February 7, 1971, Swiss men decided by referendum to let women have say in Swiss politics. The federal elections on October 31, 1971, were the first in which women could vote as citizens or stand as candidates; 11 women made it into the House of Representatives, giving them a proportion of 5.5%, and one woman took one of the 42 seats in the Senate.

What has happened since? Have Swiss women been able to take their rightful place in national politics over the past 50 years?

The ‘women’s’ election

The most recent federal parliamentary elections, held in October 2019, went down in history as the “women’s” electionExternal link. More women than ever were elected to the two houses of parliament. With a proportion of 41.5% women in the House of Representatives, the country now ranks 17th in a ranking of 191 states worldwide.

Several societal and political factors led to this success, such as the #MeToo movement and protests against the sexism of ex-United States President Donald Trump. In Switzerland, womens’ strikes and mounting climate change activism also led to more women being elected.

Click here to read the full article published by Swiss Info on 3 February 2021.

South Asia has elected its share of prominent women politicians. But what has that meant for gender equality and women’s rights on the ground?

With Kamala Harris assuming office as the United States’ first female vice president this month, conversations have been renewed over the role of women leaders in politics – particularly in South Asia, given Harris’ Indian heritage. South Asia has seen many female politicians and even elected them as heads of government, from Indira Gandhi – the first and only woman prime minister of India – to Benazir Bhutto – the first female head of state of a Muslim country and twice premier of Pakistan – despite being home to largely patriarchal and male-dominated societies. These women leaders, however, have strong dynastic backgrounds that boosted their political careers. There are also questions as to whether their tenures have been any different from their male counterparts’ or have led to any significant changes on the ground concerning women’s rights and their better representation in government and society.

A recent online cross-border discussion hosted by Himal Southasian shed light on female representation in South Asian countries and discussed how women leaders’ ideologies and governance have shaped politics. Speakers also talked about the challenges women face today as leaders and political workers in these countries. The discussion was moderated by Indian journalist, writer, and editor Luxmi Murthy.

Click here to read the full article published by The Diplomat on 28 January 2021.

The year 2020 will be remembered as one of the most consequential in generations: the COVID-19 pandemic devastated lives and livelihoods; millions protested across the country for racial justice following the murder of George Floyd; and the U.S. presidential election gripped the body politic for months.

But 2020 was also the centennial of one of the most important civic events in American history—the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibited denying the right to vote “on account of sex.” After 70 years of organizing and struggle by generations of women, the amendment’s ratification in August 1920 paved the way for millions of women to participate more fully in national elections and in the economic life of the nation. Although imperfectly implemented due to racism, sexism, and other factors, the expansion of the franchise opened new possibilities for women in their roles in the economy and society, and represented a victory in the long march toward gender equality.

To celebrate this milestone, but also to analyze the forces that have kept the United States from reaching true equality, the Brookings Institution launched “19A: The Brookings Gender Equality Series,” a collection of 19 essays by Brookings scholars and other subject-matter experts that analyze how gender equality has evolved since the amendment’s passage and explore policy recommendations to end gender-based discrimination. Visit brookings.edu/19A to find links to individual essays.

Click here to read the full article published by Brookings on 6 January 2021 and to earn more about the essays and the themes they explore.

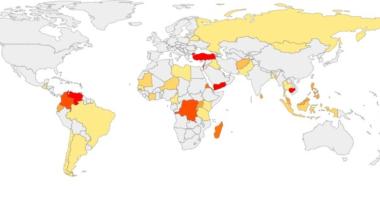

Tool by Make Every Woman Count that monitors elections in Africa.

See it here.

MPs can sometimes be subject to human rights violations, ranging from arbitrary detention and exclusion from public life to even kidnapping and murder in the worst cases. The IPU has been defending MPs in danger for the past 40 years through its Committee on the Human Rights of Parliamentarians.

The map below shows the latest alleged violations of MPs' human rights currently monitored by the IPU. Clicking on a country leads to the page of the parliament, from where you can access the latest information about the case.

See it here.